“The tunes in this album are personal impressions from the Quartet’s tour of Japan, Spring 1964. No one in a brief visit can hope to absorb and comprehend all that is strange to him. Sights and sounds, exotic in their freshness, arouse the senses to a new awareness. The music we have prepared tries to convey these minute but lasting impressions, wherein the poet expects the reader to feel the scene himself as an experience. The poem suggests the feeling.” – Dave Brubeck, 1964

Earlier this week, I excitedly rushed home from work after getting notice that my most recent Vinyl Me, Please shipment had arrived at my doorstep. I’ve been a continuous subscriber to the Essentials “track” for 3 months now, though I think I’ve actually swapped for other albums all but once (this month, I stuck it out for QOTSA’s Songs for the Deaf), and I’ve been an on-again/off-again subscriber since Demon Days dropped in 2017. This was my first time actually adding a supplemental track, and I did so for 2 reasons. First – last month, I swapped out of Flaming Lips for Art Blakey and was absolutely floored by the mastering and pressing quality. I’ve long been a vocal advocate for all-analog vinyl releases (I actually pressed VMP’s CEO on that topic when he did an AMA a year or so back) and I was very happy when the Classics subscription launched and went on with mostly (all?) AAA releases. The second reason I added the Classics track this month was because it was from the Dave Brubeck Quartet. For those uninitiated with Jazz, let me clear something up for you: if you have the chance to add more Brubeck to your collection; you do it without hesitating!

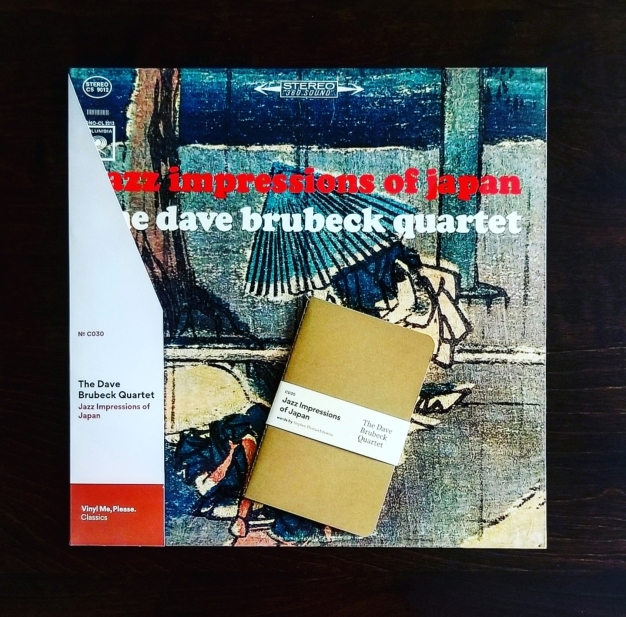

The album, which is pictured above, is 1964’s Jazz Impressions of Japan. This was the 3rd of 4 albums from the Quartet in the “Impressions” series. The others were, in order, “U.S.A.” (1957), “Euraisia” (1958), and “New York” (1964). At the time of the release of “Japan“, the Quartet was made up by Dave Brubeck on piano, Paul Desmond on alto sax, Joe Morello on drums, and Eugene Wright on bass. This was the most well-known iteration of the group, with Brubeck and Desmond being original members, and Morello and Wright joining in 1957 and 1959; respectively. The compositions and recordings were heavily influenced by their time spent in Japan as part of the US State Department’s Jazz Ambassadors program in the late 50’s/early 60’s. The program was intended to improve the image of the United States throughout the world during the Cold War. Other “ambassadors” included Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman, and Duke Ellington. Many would recognize the iconic photo of Satchmo playing in front of the Sphynx, which was taken during his 1961 tour of Africa as part of the program.

The album blends folk melodies of Japan, utilizes the Eastern scale, and borders on exotica at times; but it still retains the anti bebop/hard bop signatures of West Coast Jazz, which Brubeck was the poster child of (quite literally, appearing on the cover of Time in ‘1959). It was a true “East meets West”, in the most delightful of ways. From the opening of “Tokyo Traffic”, with Morello’s woodblock hits and gong-work, you feel as if you’ve warped from a university jazz hall to the center of a bustling Asian metro; if not with a hint of stereo-typed perceptions of what Asia was to Americans at the time. But as the song continues, you are brought right back to your western comforts, with Desmond smoothly interpolating “God Rest Ye Merry gentleman”. On the album goes, with only the tune “Zen is When” stepping slightly into a more “exotican” sound. The album is pure bliss to listen to, but as the VMP liner notes indicate, this album is a little under-loved. It was just one of over 2 dozen albums that would be released and tied to Brubeck’s name. It seems to have been lost a bit in the shuffle, even by Brubeck and the Quarter themselves, as only the final track – Koto Song – became a standard tune for the group in future performances and recordings.

The vinyl release this month became the first time the album was reissued on the format since 1980, and just the 3rd time being reissued since the original 1964 release. VMP had Ryan K. Smith cut the lacquers from first generation master tapes at Sterling Sound, and the album was pressed at QRP – all of which generally makes for a high-quality release. RKS is one of the better mastering engineers in the game, and QRP is far and away the best pressing plant going right now. The scans used for the album jacket actually appear to have printed artificial ring-wear (visible on the bottom-center part of the jacket), but the resolution is quite nice. The labels on the wax are the classic Columbia “2-eye”; noting “360 Sound”. The disc comes in QRP’s branded poly-inner sleeves and the vinyl appears to be thick; 180g weight. It’s a fairly premium-feeling package, which is very nice at the $23 price-point for an add-on subscription. As I sat down to give it a first listen, I took out the listening note (a very nice touch, I might add), and read a bit before dropping the needle.

The equipment I played the album on is as follows:

- Turntable: Pro-Ject Debut Carbon w/ Acrylic Platter

- Cartridge: Ortofon 2M Bronze, nude fine-line

- Phonostage: Parasound PPH100

- Receiver: Marantz SR7000 (using Direct mode for analog inputs)

- Speakers: Klipsch KG4

As the needle dropped, surface noise was virtually non-existent. There was, however, some decently audible tape-hiss once the track began. This is one of the down sides to an analog format and analog source – you have degradation in source quality over time and if you do not bring digital elements into the process, you will replicate that degradation into your lacquer. It’s a trade off, and in this case I think it is worthwhile, because as the music started I was awed by the “realism” of the sound. Morello’s woodblocks sounded incredibly life like, and the gong’s ring was fully audible and un-distorted. I’ve long maintained that many percussion instruments, like a gong or any drumkit cymbal, are some of the most difficult instruments to completely and naturally replicate on a consumer-level media format. But when it is done right, the result is magical to hear, and it really completed the “in the room” feel of a well mastered record. The amount of detail on this album is quite impressive – it’s a testament to the record itself, but also to Smith’s mastering. There are multiple times when you can hear Wright’s bass strings being plucked, as well as an instance when you can hear wood creaking (I think it is from the bass, but it could also be the floor, or perhaps another instrument). Again, this all adds to the realism in sound. All in all, it is a wonderful representation of an underappreciated album by legendary musicians. The folks at Vinyl Me, Please hit a homerun with this release (and special shoutout to u/storfer, who I understand is the mastermind behind the Classics track).

Unfortunately, the VMP pressing of this has since sold out. But, if you are interested, I would highly recommend giving the album a listen on your streaming platform of choice. If you like it, you can generally find original pressings in decent condition for reasonable prices. It would be worth every penny, in my opinion!

Anyways, thanks for reading, I know this was a bit long winded but I wanted to share my thoughts because I was pretty stoked about this one! If you liked this write-up, check out some of my others:

De La Soul 3 Feet High and Rising | Father John Misty Pure Comedy | Grateful Dead American Beauty | Cab Calloway